Who really built Rev John Williams’ Rarotongan ship?

Saturday 27 August 2022 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features

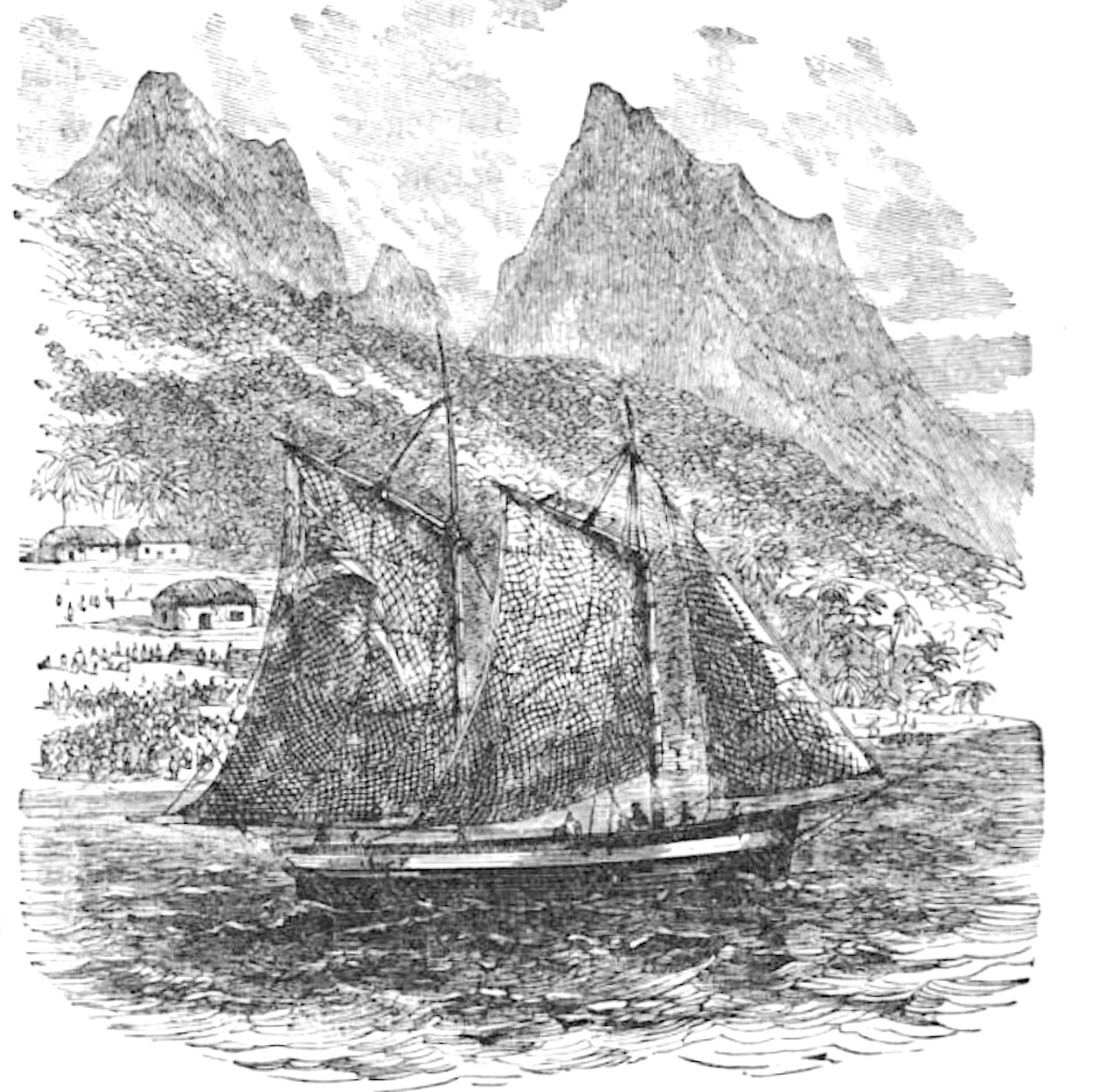

The Messenger of Peace off Rarotonga on its inaugural voyage to Aitutaki equipped with mat sails (from Prout, E., 1865, Missionary Ships…LMS, London). 22082609

John Williams was an evangelical Christian determined to spread the gospel throughout the Pacific. To this end, he constructed a ship at Rarotonga in 1827 with a ‘mechanical ingenuity’ that gave him legendary status in Britain and beyond. But who really built the ‘Messenger of Peace’?

Reverend John Williams and Mary Williams set foot on Rarotonga for the first time on 6 May 1827, (having previously observed the island only from the sea). They were accompanied by Rev. Charles Pitman and Mrs. Sarah Pitman, who were destined to be the first resident European missionaries on Rarotonga. This was four years after William’s first visit to the island onboard the Endeavour when he left behind Papehia, later assisted by Tiberio, to Christianise the population.

The Endeavour, a ship of 80 tons,had been purchased in Sydney by Williams “for the chief of Rhiatea” (Sydney Gazette, 5 April, 1822) and subsequently paid for by the sale of arrowroot by the Ra’iāteans. The chiefs of Ra’iātea hoped to use the ship, renamed Te Matamua, to trade with the growing colony of New South Wales, while periodically chartering it to Williams for mission work.

But just one year later, in 1823, Williams was forced to sell the ship after the NSW colony imposed taxes on Ra’iātean exports and the London Missionary Society refused to pay “a few hundred a year” for the ship’s upkeep. The loss of Te Matamua led to resentment against Williams from the chiefs at Ra’iātea who “called him a liar and deceiver and said that because of him, children instead of being brought forth at home were brought forth on the mountain while the parents were in search of Arrowroot for the ship” (Gunson, 1978; 137).

Now in 1827, marooned on Rarotonga, with no ship at his disposal, a frustrated Williams decided to build ‘a very large Vessel’ to recommence his missionary travels throughout the Pacific.

“Had I a ship at my command,” he wrote, “not an island in the Pacific but should (God permitting) be visited and teachers sent, to direct the wandering feet of the heathen to happiness – to heaven.” (Prout, 1842; 156).

To build a ship would involve large numbers of Rarotongans – it took, for example, 2000 men to pull the vessel over rollers to the sea at Avarua. The resident missionary Charles Pitman begged Williams “not to give the people any more work,” considering the large number of building projects already undertaken for the Church (churches, villages, schools, etc.,) during the four years of “poor treatment” of the Rarotongan people by the first two orometua (who, Pitman claimed, behaved “more like taskmasters than Christian teachers”). Pitman feared yet another large project might cause the Rarotongans to “feel a disgust against the Gospel” and turn against the mission.

Pitman was also concerned at the already heavy loss of life at sea resulting from Williams’ demands on the people. Earlier that year, Williams had sent a ‘boat’ with six men to Atituaki to bring back a larger boat which had drifted there from Ra’iātea. On its return journey the boat was accompanied by several other vessels – four of which, including one carrying Tupu Ariki of Aitutaki and the orometua Mataitai’s wife – had gone missing at sea (Prout, 1842; 204). “If this be true,” Pitman wrote, “not less than 66 persons in these three boats and 10 in the boat of Mr. Williams, have either perished or drifted….” (Pitman’s Journal, 1827;12).

The two orometua on Aitutaki responded to these losses “by breaking up all (the Aitutakians) large (ocean-going) canoes and insisting they build no more except for the purposes of fishing.”

Williams’ response was to build a larger boat.

“I determined to attempt to build a vessel,” he wrote in 1827, “and although I knew little of ship-building, had scarcely any tools to work with, and the natives were wholly unacquainted with mechanical arts, I succeeded, in about three months, in completing a vessel between seventy- and eighty-tons burden” (Prout, 1842; 174).

The vessel, constructed in the front yard of Williams house at Avarua, was a two masted schooner, measuring “sixty feet in length and eighteen feet in breadth” with an eight metre (26 feet) beam (Williams, 1838; 150).

It was “built entirely of tamanu and about fifty or sixty tons, quite sharp … I call her the Messenger of Peace” (Prout, 1842; 172). Elsewhere he refers to the ship as “The Rarotonga” and the “Olive Branch.”

Some months later, in early January 1828, the boat was ready for launch but after initial sea trials, during which the foremast broke in half, and the ship took in water, the vessel returned to Rarotonga for strengthening using additional iron brought from Tahiti by the recently arrived Rev. Aaron Buzacott.

In mid-February, the Messenger of Peace made its inaugural voyage to Aitutaki. Maretu says that Williams was accompanied on this voyage by the Arikis –Makea, Pa, Tinomana, and Karika as well as the chiefs of Tupapa, with the ship visiting Aituitaki, Manuae, Mauke, and Atiu.

In March, 1828 Williams set out on the longer voyage to Ra’iātea, accompanied again by Makea and “two immense idols” (Tangaroa god staffs) from Rarotonga.

Images of the Messenger of Peace in Williams’ best-selling book A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises (1838)show the ship with large sails made of matting (the traditional sail cloth of Polynesian voyaging) adding to the image of an ingenuously improvised vessel. However, matt sails were used only on the inaugural trip to Aitutaki. For the longer trip to Ra’iātea, “having nothing but matt sails I thought it not prudent to allow it (to go ahead) and have at a considerable expense purchased one good sail – it has cost me £25 – and procured a sailor.” (Williams, February, 1828).

In another letter he writes, “I was obliged to give thirty pounds for one sail – besides purchasing rope blocks, etc.,” (presumably from a passing ship). “The other sails I purchased with (sales of locally made sennit) rope made on the spot.” Both masts were thus equipped with standard canvas sails for the voyage to Ra’iātea and subsequent journeys.

Romantic notions of Williams at the ship’s helm are also dispelled by a quick look at the financial records of the ship which include “hire (of) a Captain (Captain Palmer) at Ten Pounds a month and a sailor at three.” (Williams, 18 April, 1828). The rest of the crew were Rarotongans supervised by Makea who accompanied Williams on many of his journeys.

In his account of the building of the Messenger of Peace, Williams claims: “I knew little of ship-building” and “had scarcely any tools.” Yet at the age of fourteen Williams had been apprenticed to a London ironmonger and was no stranger to the foundry workshop. As the Pacific historian Niel Gunson recounts, “by the age of eighteen he had not only become manager of the shop but mastered the mechanical skill of the workshops as well” (Gunson, 1972; 75).

On Rarotonga, he put his iron working skills to use, constructing a set of smith’s bellows, a forge, a turning lathe, and other iron work made from melting down old axes, iron hoops and an iron chain cable from the ship ‘Cumberland’ left behind by Captain Goodenough in 1814.

With regard to his knowledge of ship-building, on first arrival at Mo’orea in 1817, Williams had successfully completed construction of the missionary brig Haweis and continued to practice boat building at his own mission station at Ra’iātea, writing in August 1819, that “Requiring a larger boat than that which I built at Eimeo (Mo’orea) that I may visit Tahaa, I have completed one sixteen feet long.” (Prout, p.53). This was a full eight years before construction of the Messenger of Peace.

Building an 80-ton ship required trees to be felled, logs to be hauled, timbers adzed into planks, the ship’s keel framed, the ribs fixed, the hull dressed, the deck laid and the masts shaped and hoisted. This in turn required ownership of a forest resource and the ability to mobilise a workforce to harvest it, as well as undertake the hard-physical work of actual boat building. The first missionary ship built in Tahiti and completed by Williams – the brig Haweis –required the collaboration of Pomare II with his power to mobilise massive physical and human resources. Equally in early 19th century on Rarotonga, such a project could only be completed at the command of an ariki, in this case Makea Pori.

One of William’s contemporaries, the Rev. Charles Barff astutely noted that it was Makea Pori – not Williams – who built the Messenger of Peace, handing over the completed vessel to Williams for missionary work. “Makea,” wrote Barff on 27 May, 1828, “with Mr. Williams judicious directions, has built a large vessel at Raratoa (sic) which is given up to Mr. Williams as a missionary vessel. The length is 10 fathoms and width in proportion.” (Letter dated 27 May, 1828).

Similarly, Pitman who was on Rarotonga as the vessel was being built, reported to his directors in London – “It has been built entirely by the natives of this island and has not hitherto cost twenty shillings.”

Lessons learned in building the Messenger of Peace were not lost on Makea Pori and after 1839, by the new ariki Makea Davida, both of whom quickly recognised the autonomy and prestige gained by other chiefs in neighbouring islands through ship ownership.

Makea Pori accompanied Williams on many of the Messenger of Peace’s voyages as patron and provisioner of the ship and supervisor of the Rarotongan crew. On one trip from Rarotonga to Ra’iātea, he attended a meeting of all the chiefs of the Leeward Islands who “have built so many large and strong boats” (Barff, 26 May, 1828).

A number of young Ra’iātea men who had helped Williams on his earlier ship building projects had branched out into business on their own. One was rebuilding a small schooner owned by Mahine, principal chief of Mo’orea– “having put in beams, knees, deck, etc.,” so professionally that “no one but an experienced builder could tell that is had not been done by an English shipwright” (Prout, 1842; 229).

Another vessel of forty tons was being built by Ra’iātean shipbuilders for Tamatoa ariki of Ra’iātea. Yet another vessel built at Tubuai had been brought down to Ra’iātea to be finished. And it was at Ra’iātea that the Messenger of Peace underwent several months of strengthening and refitting after its initial arrival from Rarotonga (Williams, 1838;217).

“The king’s quay,” wrote Williams at Ra’iātea, “is like a little dock yard” (Prout, 1842; 229). In total “Ra’iātea acquired its own fleet of seven sloops and schooners” (Chappel, 1997; 12).

Makaea would not have been oblivious to all this on his visits to Ra’iātea, Huahine, Bora Bora, and Tahaa. Experience of European ships “set new levels of aspirations for status-conscious chiefs as well as for indigenous craftsmen” wrote Marjorie Crocombe and Harry Maude. “The canoe-makers craft was adapted to the new art of ship-building.”

Makea Davida, who became ariki on the death of Makea Pori in 1839 saw the possibilities of emulating the chiefs of neighbouring islands, by building and outfitting his own trading schooner. In 1843, long after the Messenger of Peace had been sold off, the Rarotonga mission was chartering “the small schooner belonging to Makea” to visit the outstations at Aitutaki, Atiu, Mitiaro and Mauke (W. Gill, Mangaia, 1843).

Later that year, Makea’s ship was chartered by John Williams’ son when his own trading ship The Samuel and Mary was holed on the reef at Rarotonga. Williams Junior further engaged Makea’s ship for trading journeys to Samoa and Sydney.

Building his own ship earned Makea money and prestige and allowed him to escape the strict missionary laws of Rarotonga. In September, 1845 Buzacott noted that “In July 1844, he (Makea) left in his schooner for Tahiti and was absent for more than three months.” On his return, he was found to be strongly addicted to alcohol, consuming “a bottle of brandy in less than two days … His stomach could retain nothing.” The resulting illness proved fatal, and he died on 11 June 1845. His last words were “E Parakoti e, tei ‘ea au?” Oh Buzacott where am I?

Over its five years of mission service, the Messenger of Peace, in its livery of green paint donated by the British warship HMS Seringapatam, made multiple visits to mission outstations in the Leeward and Cook Islands, carrying the Gospel to Samoa, visiting the Marquesas and Tonga, and attempting to land teachers at Niue.

In 1833, in anticipation of Williams’ return to England, the ship was repaired at Rarotonga, and sold at Tahiti, with instructions to charter another vessel to take Williams and his family from Rarotonga to Tahiti in April 1833 for their onward voyage to England.

According to Williams’ biographer, (Prout, 1842; 267-8) “as the time appointed had passed and no ship appeared, he (Williams) began to think seriously of building another (ship) and probably would have done so … had not an American, then in the island, previously made an unsuccessful attempt; and being unable to finish the work he had begun, he very gladly transferred the undertaking for a compensation (of $250) to Mr. Williams, who speedily completed the vessel, and sailed in her with his family to Tahiti.”

It seems that once again Makea had come to Williams’ rescue, providing him with the resources and labour needed to complete a second vessel – a degree of support Makea had seemingly refused or discontinued in the case of the young American.

“I built a ship” claimed Williams who became widely celebrated for his ingenuity in doing so on a remote Pacific island. “In all the long story of the building of ships,” exclaimed one account of The Messenger of Peace “(none) seemed more impossible to achieve” (Matthews, 1915).

But both Williams and the young American would have been the first to concede that no big project – whether building a church or constructing a ship – could succeed on Rarotonga without the active support of an ariki. John Williams brought technical knowledge to the shipbuilding process, but it was Makea Pori and the people of Avarua who built the Messenger of Peace.

References

Prout, E., 1843, Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, John Snow, London

Gunson, Niel, 1972, “John Williams and His Ship – the Bourgeois Aspirations of a Missionary Family.” In D. P. Crook, Questioning the Past, UQ Press, St. Lucia

Gunson, Niel, 1978, Messengers of Grace, Oxford University Press Melbourne

Matthews, Basil, 1915, John Williams the Shipbuilder, Oxford University Press, Oxford