The Scottish kumete from Atiu via Tahiti

Saturday 14 October 2023 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Art, Features, Weekend

The massive Atiu kumete in the Edinburgh Museum. 23101341

Standing in the middle of the Grand Gallery of the Edinburgh Museum is the largest kumete in the world. But how did it get there, asks Rod Dixon.

Prominently displayed in the Grand Gallery of the Edinburgh Museum, in Scotland, is an impressively large canoe-shaped object that has its origins in the Cook Islands, and specifically on Atiu.

Made of tamanu, the object is 12 foot long, more than 3 feet wide and 3 feet high with a capacity of 280 gallons.

The object is a “pudding bowl” or kumete, known as uete vaka roa on Mangaia and paroe on other islands like Mitiaro. According to Te Rangi Hiroa, “The canoe bowls were used for mixing food in quantity, for dying bark cloths by immersion, and for storing water.”

Tamanu kumete from Atiu, in the Grand Gallery of the Edinburgh Museum (photo - National Museums of Scotland)/ 23101337

The Edinburgh kumete once belonged to Parua ariki of Atiu. It was gifted in 1871 by Parua to Te Tuanui-rei-ai-te-raiatea of Ha’apiti, Moorea, a niece of Queen Pōmare IV. The kumete was gifted by Parua probably on a tere visit, undertaken on one of the schooners acquired by Cook Islands ngati in the latter half of the 19th century.

The recipient of the kumete, Te Tuanui-rei-ai-te-raiatea (1842–1898), was the daughter of Alexandre Salmon and Ari’i Taimai. Salmon (1820–1866) was an English businessman of Jewish ancestry who became secretary to Queen Pōmare IV and married her twenty-year-old adoptive sister Oehau, the Ari’i Taimai.

One of their daughters, Te Tuanui, married the Scottish merchant John Brander (1814–1877) at the young age of 14. This was an arranged marriage that cemented the social and political position of the Salmon/Brander business empire, comprising stores, warehouses, a fleet of schooners and plantations in Pape’ete and the islands.

Te Tuanui-rei-ai-te-raiatea (1842–1898). 23101338

Brander was a major importer of Cook Islands labour working on the Brander plantation in Tahiti during the second half of the 19th century. It was around this time, that Atiuans and Mangaians, working in Tahiti, acquired sections of land in Pape’ete, in the Patutoa district for Atiu and the Taunoa district for Mangaia.

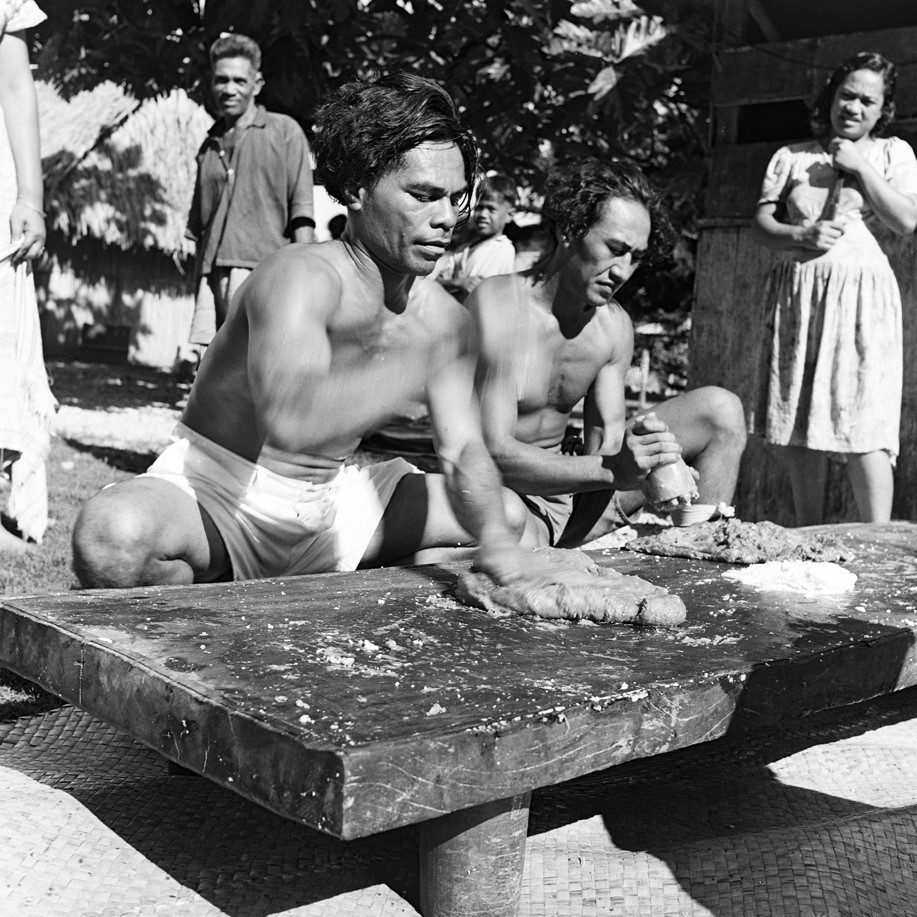

On Mangaia, poi is made from mamio or taro that has been cooked, then mashed on a special platform (pa'ata) called papā‘ia A stone pounder (reru) is used to mash the mamio, which is then mixed with coconut sauce. The small white pile in the photo is ota or grated coconut flesh (photo – D. S. Marshall Archive, USP Cook Islands Campus). 23101340

It’s been suggested that Te Tuanui had some association with the Patutoa lands and that the gift of the Atiu kumete acknowledged this relationship.

The Atiuan kumete - Height 91cm, Length 366cm, Width 97cm Capacity 280 gallons

(photo - National Museums of Scotland). 23101339

In 1874, Alexandre Salmon’s nephew, John Mortimer Salmon, took up residence in Rarotonga as a representative of the Brander company which, according to some accounts, operated coconut plantations and a copra export business in the Cook Islands. John Mortimer Salmon married Tinomana Mereana ariki, and together they adopted John Mereana Taripo, the future owner of numerous Rarotongan businesses, including the iconic Empire Theatre. Salmon himself was one of the driving forces behind the purchase and refitting of the Arorangi schooner “City of Arorangi” later renamed the “Maungaroa.”

In 1878, following John Brander’s death, Te Tuanui married one of Brander’s partners, the Scotsman George Darsie. In 1892 they retired to live in Darsie’s hometown of Anstruther on the Firth of Forth in Scotland, bringing the Atiuan kumete with them. Te Tuanui died six years later at the age of 55. The kumete was subsequently sold by Darsie to the Edinburgh Museum. It is reported to be the largest Polynesian bowl in any overseas collection.

Making poi – a recipe by Ivi’iti ‘Aerepō

The Edinburgh kumete is described as a ‘feast bowl’ and, with a 280-gallon capacity, held enough poi to feed a village. Poi can be made from a number of ingredients, including breadfruit, banana and taro. The following poi māmio recipe is from the late Ivi'iti 'Aerepō of Mangaia.

“First of all, you have to gather coconuts, some dry, some nearly dry. The coconuts are then husked and the woolly fibres are scraped off the shell, otherwise the fibres will fall into the grated kernel. Five hundred to one thousand nuts are needed for the occasion, especially if the poi is for the use of the whole village. After the nuts are prepared, some big baskets are woven out of coconut fronds. The baskets are lined with banana leaves and/or the leaves of the ti plant. The grated nut ('akari) is placed in the baskets and fermented.

For fermentation, some crabs (tītīrōtai) and some fresh water crayfish (kōura vai) are collected. These are pounded together and mixed into the grated nut. The baskets are then covered with leaves, tied with kiri'au and then left until the mixture is ready for use in about one week.

Next, a big umu is prepared. Then the māmio (taro) is gathered and placed in the umu without peeling. When the mamio is cooked the women gather around the umu and peel by hand. At the same time the men are preparing the papā‘ia, a flat wooden platform used for pounding the taro on. When this is prepared the men are arranged around the papā‘ia. Four or five papā‘ia are lined up in a row. Men squat on both sides with a woman between each man. Everybody has a job to do.

The cooked māmio and coconut mix (ota) are then brought and three to four lots of ota are placed in the middle of each papā‘ia to mix with the pounded taro. When the men on both sides are pounding, they pound in special rhythms and the women dance as they supply the taro to the men. A watchful eye is kept by one woman to make sure no man runs out of taro or ota and she signals if there is a man in need. Other women wipe the sweat off the men.

The last job is carried out by a group of women. They mix the finished, pounded material (kareru) with some more ota and this action is called tāpoa. (A reru tāpoa or smaller penu is used for this stage). The poi is now ready and can be eaten immediately or kept for a long time, the longer the sourer. A little sugar or ripe banana can be added.”

Kumete, such as the massive Edinburgh bowl, could be used to mix, store and serve poi.

References

Ernest Salmon, 1964, Alexandre Salmon (1820-1866) et sa femme Ariitaimai (1821-1897)

Publications de la Societe des Oceanistes, Tahiti