How Mangaians helped rescue Raro’s economy

Saturday 18 February 2023 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, In Depth, Memory Lane

Foreign settlers (c.1900) - a generation later, they had become Rarotongan household names. Those pictured include Jean Dominique Peyroux, William Estall, and Ah Taripo. (Source, Dick Scott, Years of the Pooh-bah). 23021709

At the beginning of the twentieth century migrants rescued Rarotonga’s population and economy, then in apparently ‘terminal’ decline. Within a few decades these migrants had become established Rarotongan families, traditional landowners and custodians of the culture. Is a similar process currently underway?

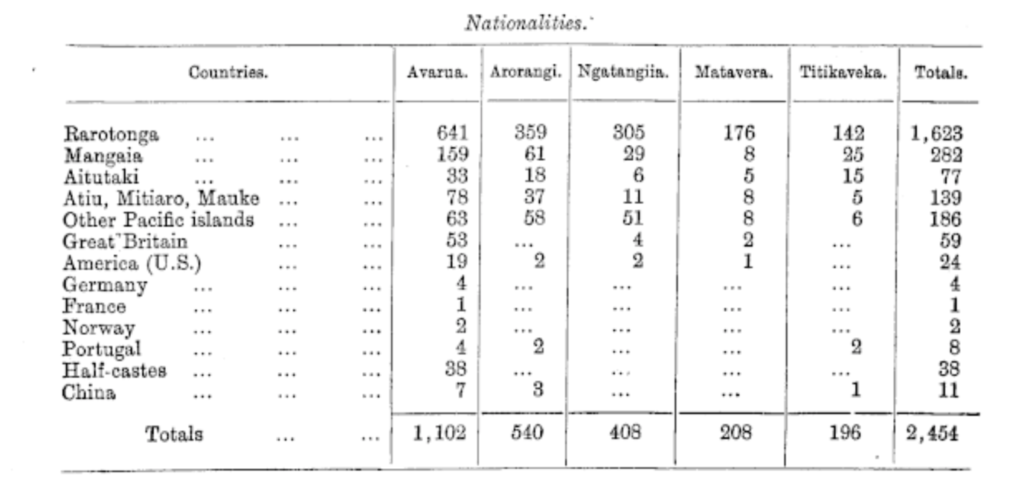

Throughout the 19th century, Rarotonga’s population declined more dramatically than its sister island of Mangaia (see Table 1 below).

Colonial administrators of the era considered Rarotongans a “dying race” and, according to Ron Crocombe, the Rarotongan people themselves “seem to have been convinced that their extinction was a ‘forgone conclusion’” (1964; 97). Words like ‘extinction’ were commonplace – the New Zealand Herald, at the time, writing of the ‘rapid decrease and probable extinction of these (Cook Islands) people in the near future…” (New Zealand Herald, 12 September, 1891).

Throughout the nineteenth century, Rarotongan deaths continuously exceeded births. In 1843 the ratio was 44 deaths for every 10 Rarotongan births, leaving the population struggling to replace itself (Gilson, 1980: 38).

In 1901, deaths in the districts of Matavera and Arorangi exceeded births by 200 per cent (AJHR 1902A-3; 11). At the same time Takitumu was experiencing perhaps the island’s most severe population loss through out-migration, leaving huge tracts of agricultural land uncultivated. A trade depression in the 1890s accelerated this exodus, leading to regulations controlling the number of workers who could leave the Cook Islands to work overseas.

Yet, despite ‘terminal’ population decline, labour shortages and a seriously underperforming agricultural sector, Rarotonga had, by the turn of the twentieth century, become the numerically and economically predominant island of the Cook Islands. This was for a number of reasons.

The first reason was the existence of natural reef passages at Ngatangiia, Avarua and Avatiu which facilitated trade and transport. Most of the other southern group islands were reef bound and perilous to shipping.

A second reason was the decision to locate the London Missionary Society headquarters, and subsequently the British and New Zealand colonial administrations, around the Avarua reef passage and the later concentration of finance and infrastructure (harbour facilities, training institutions, communications etc.) in the port town of Avarua.

A third and possibly major reason was the willingness of the Rarotongan arikis – unlike their counterparts in other islands – to allow Europeans and other nationalities to live and work on the island despite the strong opposition of the missionaries. Aligned with this was a willingness by major landholding and ariki families to marry members of the settler and migrant community.

In 1881 there were 70 expatriates living on Rarotonga, mostly traders. By 1895 this had grown to 147, an increase of 100 per cent. At the turn of the twentieth century Rarotonga’s expatriate population included 32 British, 33 New Zealanders, 11 Chinese, 10 Americans, five Portuguese and three French (Census 1901). Other nationals included 75 from Tahiti, Raiatea and Borabora (rising to 241 in 1911), 35 from Rimatara and Rurutu and 31 indentured labourers from Arorae in the Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati) who introduced Rarotongans to “roro” – an arrack style liquor made from the fruit stem of the cocoanut tree (Auckland Star, 21 September 1900).

Rarotonga’s arikis were willing to lease out large areas of land to foreigners, again unlike their counterparts in the outer islands. In 1894 the Rarotonga Council resolved that “the time has come to form special settlements of people from New Zealand, who might desire to be planters of coffee or other products on the lands lying unused in Rarotonga.” A “Special Settlement” scheme planned to offer farms of 10 – 20 acres to foreign settlers. The British Resident, Frederick Moss favoured the importation of Christian Japanese settlers.

The “Special Settlement” scheme was never implemented but by 1899, 1200 acres of land on Rarotonga had been leased to foreigners, representing around one fifth of the island’s 5200 arable acres (Crocombe, 1964; 74).

Eight years later, 17 Europeans were leasing 1463 acres of arable land. The largest leases were held by an employee of Donald and Edenborough called William John Wigmore (350 acres), the government surveyor Hugh McCrone Connal (280 acres), Dr. Gatley from Rarotonga Hospital (250 acres) and Messrs. Brown (135 acres), Davis, (130 acres) and Engelke (130 acres).

Operating these sizeable plantations required labourers in numbers which the declining Rarotongan population could not supply. The small indigenous Rarotongan workforce was outnumbered by 832 mainly male migrants working in Rarotonga’s foreign owned stores, factories (cotton ginning, boat and carriage building), homes and plantations. A third of these workers were Mangaians.

The Mangaian based newspaper Te Karere noted at the time - “the population of (Mangaia) has decreased during the last five years to the extent of 280. It is largely a case of supply and demand. Mangaians have the reputation of being more industrious than the natives of other islands and, as a consequence, are in request by employers of labour.” (Te Karere, No. 13 April 1900).

In 1911, the census found “an increase in the population of Rarotonga … accounted for by the arrival of large numbers of Mangaians as labourers, and also arrivals from Tahiti and other French islands of Natives who have come to Rarotonga to settle.” In the same year, a visitor noted “Labour for plantation work, etc., is usually fairly easy to obtain, most of the men coming from Mangaia on indenture.” (The Press, Auckland, 17 July 1911).

By 1895, Mangaians comprised one quarter of the population of Avarua (Census, June 1895) many living in an improvised settlement on land at Tutakimoa rented from Tepou o te Rangi. Elsewhere Mangaian plantation workers clustered around large European plantations in Titikaveka and Arorangi.

Initially these landless outer islanders lived in ‘squatter’ camps, maintaining their separate island identities. They were often exploited. In 1911 the Rev Bond James at Takamoa, complained that “Young boys are brought over from Mangaia and other islands and are persuaded to sign on for 12 months. They are allowed to make bush-beer and live just as they like without restraint, their masters giving the worst possible example.” (James to LMS Directors, 14 April, 1911).

Rev. Bond James was speaking specifically about what he described as a “disgusting and alarming” “orgy” at the Wigmore plantation that led to the killing of More in 1911. In the subsequent court case, Matekeiti, the young son of the ruling Mangaian ariki Metuakore John Trego was a prosecution witness. At that time, Mangaians working on Rarotonga remained subject to their own island’s laws and were tried by visiting judges from their home island.

Over time, however, most outer island communities began to be absorbed into the Rarotongan population, ceasing to exist as distinctive communities (excepting Pue and Tutakimoa).

Ron Crocombe writes that, “At first these immigrants could acquire the use of land only by permissive occupation… but in the course of time some married into their host lineages and thus improved the security of the tenure of the lands they occupied.” (1964; 71). Crocombe finds supporting evidence for this in the “marked increase in uxorilocal marriages (the husband living on his wife’s land) and a consequent increase in the number of persons claiming their land rights through the mother…” (1964; 76).

These marriages, according to demographer Norma McArthur, depleted the reproductive capacity of Mangaia and other outer islands while enhancing that of Rarotonga.

As a result, a significant proportion of Rarotonga’s population today are the descendants of outer island workers and foreign settlers, inheriting land rights through their mothers. This includes a significant number of foreigners who married into ariki and mataiapo families whose descendants are today’s titleholders. Mangaians, who formed the largest migrant stream, have in later years provided Rarotonga with business leaders, administrators, educationalists, doctors, politicians, and a Prime Minister.

Similar trends continue today with ongoing out-migration from Rarotonga, accompanied by inward migration from the outer islands and overseas. In 2021, the Rarotongan population of 10,683 included 1719 people born either in NZ, Fiji, other Pacific Islands, the Philippines and Indonesia. Meanwhile the outer islands populations remain close to tipping point. Mangaia remains the most populous of the outer islands with just 471 people. This includes a working-age population of 217 (104 men and 113 women) – smaller than the staff of some Cook Islands government departments.

Once upon a time, migrants rescued Rarotonga’s population and economy from possible ‘extinction’. Within a few decades they had become old established Rarotongan families, traditional landowners and custodians of the culture. Could a migrant workforce be called upon to do so again?

References

Ron Crocombe, 1964, Land Tenure in the Cook Islands, OUP, Melbourne

Richard Gilson, 1980, The Cook Islands 1820 -1950, Victoria University Press