The Cook Islands Māori calendar

Tuesday 26 April 2022 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Weekend

Cook Islands ‘Natives hailing the reppearance of the Pleiades’ (WW Gill, "Life in the Southern Isles” 1876). 22042204

Traditionally, Cook Islanders observed Matariki as the commencement of the annual calendar, a calendar that reflected cycles of life in the agricultural economy of the south and the fishing economy of the north.

Is there anything we can learn from the traditional Cook Islands Māori calendar today?

The cycle of nature

Most people in the Cook Islands are familiar with the arāpō – the nights of the moon that influence planting and fishing. Less attention has been given to Cook Islands calendars, the months (marama) and seasons (tau/‘yam cycle’) of the Cook Islands year. (The Cook Islands calendar did not observe days of the week).

In the northern group, the calendar emphasised the ebbs and flows of fish stocks and sea and wind conditions, while, in the southern group, the primary focus was on the planting, growth, ripening and harvesting of fruit and vegetables. In both cases, the calendar reflected the rhythms of daily life, economic and cultural patterns and religious practice alongside the cycles of nature – the months when fruit and plants showed seasonal signs of life (e.g., Ma’au on Mangaia, the fifth month of the winter season); the month when turtles land to lay their eggs (following Matariki in Pukapuka); the months when fingerlings are plentiful (e.g. the arrival of ika tauira with the new moon in February); Iringa (July/August in Atiu) - the time for māroro spawning, the māroro tu, (Mokoroa, 1981; 269); the movement of the kuonga in Mangaia – the annual rotation of an area of calm seas (tai mate) (May to July in the north, bringing octopus; August to October in the West; December to February in the south; March to May in the East) – said to be influenced by the apparent rotation of the Milky Way; the time of year when crabs go to the beach to spawn (Karai‘i kō‘ā - the months of 'Akā'u and Ōtunga on Mangaia); times of plenty when religious feasts and festivals, including the first fruits or harvest festival were held – Iringa in Mitiaro, ‘Akā‘u in Mangaia); times of scarcity and when to start planning for the lean months; the dark months, the windy and cold months, te tau o te mata tonga. Observance of this calendar was accompanied by the generational transmission of knowledge and rituals associated with seasonal practices and occurrences.

This situation changed after Christian missionaries introduced the Gregorian calendar, a solar calendar of 12 months with 28–31 days each. A regular Gregorian year consists of 365 days, with short and long months, and an extra day added to February every leap year, an example of intercalation which Cook Islanders also used in their calendars. Overlaying the Gregorian calendar, the Christian liturgical calendar marked its feast days and seasons, including Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter, etc. Christianity also introduced to the Cook Islands the notion of a seven-day week.

The rising of Matariki

In the Cook Islands, the annual cycle, or calendar started with the rising of Matariki or the Pleiades – a cluster of stars (or asterism) seen rising on the eastern horizon in the evening twilight. The missionary Wyatt Gill places the rising of Matariki around the middle of December (Gill, 1876; 317) - the ‘acronychal rising’ - at a time of seasonal fertility and reproduction in this part of the world. The rising of Matariki was followed by the first fruits ceremony of takurua mata’iti.

Further north, in Rakahanga, according to Buck and his informants Haumata-tua and Aporo-ariki, “the whakaauanga or morning rising of the Pleiades in June (its ‘heliacal rising’ in the morning twilight) was the guide to the commencement of the year, in the month of Whakaau….”

“No mention is made of the Pleiades in the November-December period, so that the evening rising of that constellation was of no significance in the Rakahangan calendar … In May the Pleiades disappear and cannot be seen at any time of the night. Their reappearance in June in the eastern sky before sunrise is thus the reappearance of that which was lost and is hailed with singing and dancing” (Buck,1932a ; 226-7).

Gerald McCormack notes that the acronychal rising of the Pleaides occurs in mid November rather than mid December, while writers such as Craighill-Handy have argued that the rising of the Pleaides “was taken only as a general indication of the approach of the season of plenty … (which was) determined by the rainy season ... The old accounts speak of an approximate time (for first fruits rites), giving the leeway of a month …”

Each month was associated with a named star or constellation – only 12 are recorded – following a near identical sequence in the northern and southern islands – Matariki (Pleaides), Takurua (Jupiter?), Vero-matau-toru, Ika vaerua, Nga tarava (Milky Way), etc - the sequence commencing in June in the Northern Cooks and November/December in the Southern Cooks. People in both regions would have observed the same stars at the same time but may have given calendric significance to different aspects of their appearance in the night sky, as in the case of Matariki.

Intercalation

According to the missionary Wyatt Gill, on Mangaia, “The knowledge of the calendar belonged to the kings.” The need for an arbiter, such as an ariki or high priest, to set the annual calendar, arose in part from the need to synchronise observations of the year measured by moons (the lunar calendar) and the year as indicated by the seasons and the sun (the solar calendar).

The process of adjusting the length of a month (adding or subtracting a day or days) or the length of a year (adding or subtracting a ‘month’ or ‘months’) to ensure the synchronisation of the solar and lunar calendars is known as ‘intercalation’.

Gerald McCormack explains the process of intercalation as follows – “The seasons are determined by the Sun which has a year of 365 days. Thus, people using a repeating Lunar-month calendar would have found that 12 Lunar months (354 days) was too short, and 13 months (384 days) was too long. Every year they had to make an adjustment to keep it synchronised with the actual Solar cycle. The simplest solution was to have 13 named Lunar-months and periodically discard the 13th month.”

In Mangaia, Manihiki and Rakahanga the names of 13 months are recorded while for Tongareva, Aitutaki and Rarotonga the names for only twelve months are known. In all islands intercalation was used. Buck writes that, in Rakahanga, a year might vary in length from 356 to 372 days.

Additionally, natural events which helped synchronize Islands’ calendars, such as the onset of the rainy season, did not always arrive with mathematical exactitude. Consequently, a degree of internal flexibility was needed.

Each month had its own name, which often varied between islands. The months were also commonly listed numerically, for example - “Kautua kerekere – the 12th month of the ancient Māori year”.

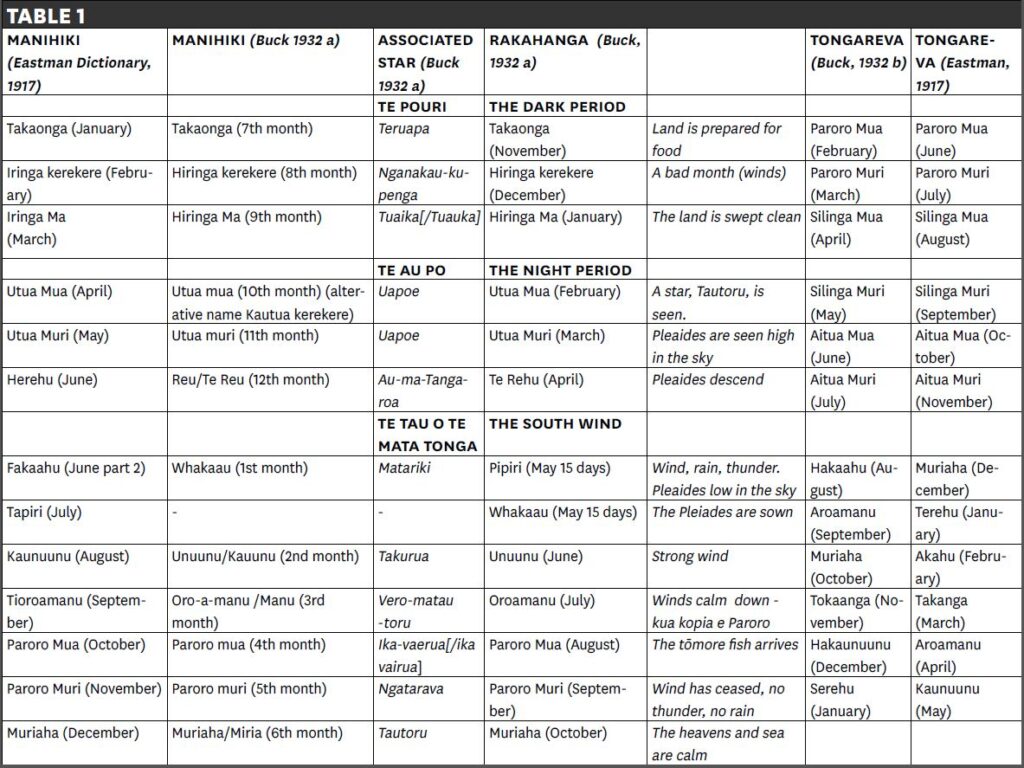

Manihiki, Rakahanga and Tongareva (Table 1)

The names of the months on Manihiki, Rakahanga and Tongareva were recorded in the early twentieth century by the Rev. G.E. Eastman and Sir Peter Buck. Their lists are broadly similar though, on occasions, they use different spelling. However, the two writers differ significantly in aligning the Māori months with western calendar months.

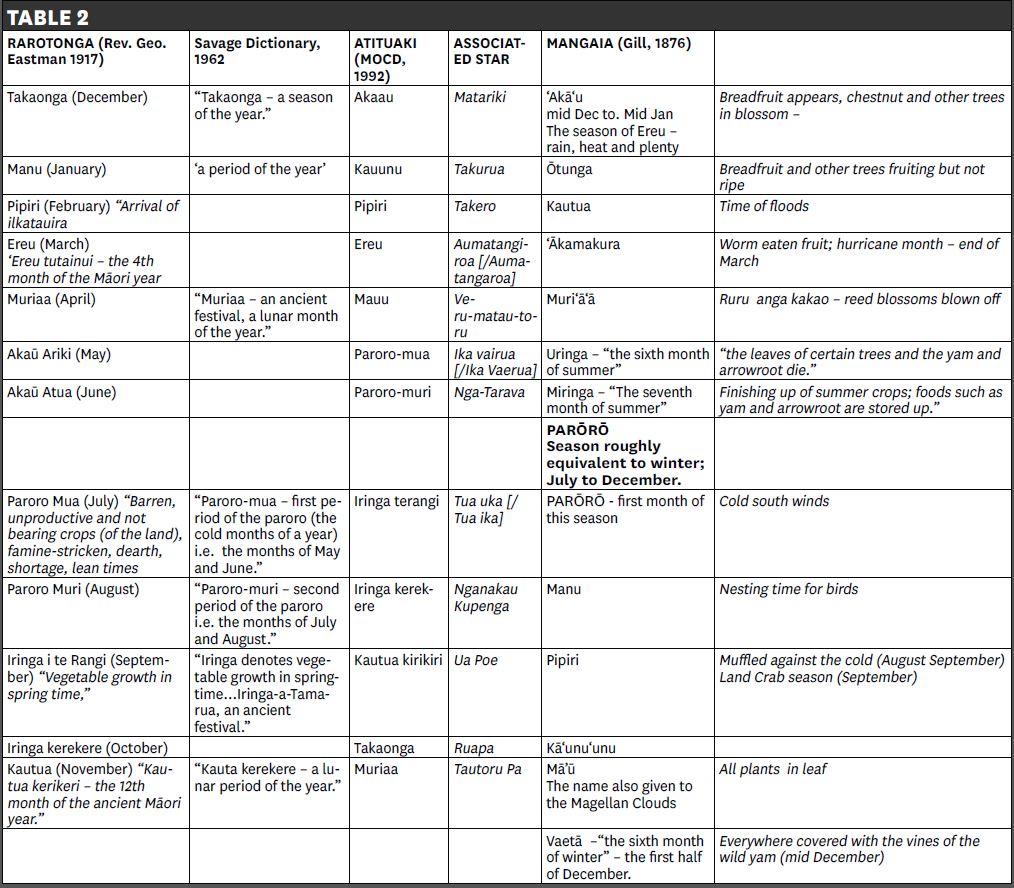

Rarotonga, Aitutaki and Mangaia (Table 2)

The Māori names of the months on Rarotonga were recorded in the early twentieth century by the Rev. G.E. Eastman and less systematically by Stephen Savage in his Rarotongan dictionary. Those for Aitutaki appear in the publication “Te Are Korero o Aitutaki” (MOCD,1992), while the list for Mangaia was collected by the Rev. William Wyatt Gill in the mid 19th century. A number of the Māori names of the months are common to all three islands (and, to a lesser extent, Atiu) – namely, Paroro, Iringa/Uringa, Ereu, Muria’a, Pipiri and Aka’au /Akāu/‘Akā‘u – but are sequenced differently. For example, the Eastman/Rarotonga and Aitutaki lists align the month Pipiri with February, whereas Savage records “Pipiri – a period of the year, said to be the months of September, October, November.” There are similar difficulties in aligning the Māori months with western calendar months, as experienced in the northern lists in Table I.

For Pukapuka, Beaglehole (1938: 24-25) writes that “The native Pukapukan year was divided into seasons (vaia).” The new year was announced by the morning (heliacal) rising of the Pleaides about mid-May. This was a signal for the commencement of six months of pleasure – ono maina utuutu (May/June to October/November) followed by ono maina ya (November to April) a six months period of stagnation. During ono maina tututu “The cool Trade Winds blow steadily from the South East, deep sea fish are plentiful and the sea outside the reef in the lee of the atoll is always calm enough to render it possible to catch these fish.” In contrast, the six months of ono maina ya “is a period of heavy and changeable winds, possible hurricanes, excessive heat and sultry weather. Deep-sea fish are not plentiful and heavy seas sometimes make fishing arduous.”

Another Pukapukan way of marking the year involved three seasons –

- The rainy season known as te vaia yua - from November to March – the winds swing round from the south to the northwest, fishing is bad, good growth of trees, nuts, and talo; time to repair roofs;

- The season for fair weather known as te vaia lelei – March to June – plenty of food, good fishing, still rainy

- The season of scarcity known as te vaia to te onge – July to October – little rain, the talo turns yellow and produces few tubers, deep sea fishing is good but water and talo are scarce.

For Atiu, Bill Evaroa has recorded four of the months of the Atiuan calendar –“tetai o te au tuatau e ā o te mata’iti

Paroro – the cold season

Iringa – spring, season of fruit

Pipiri – season of pollination

Aka’au /Akāu– season of release of land [harvest].

I have been so far unable to find recorded the remaining months of the Atiuan calendar or those of Mauke and Mitiaro.

Contemporary relevance

In Australia the Government’s national research body, the CSIRO has been working with indigenous Australians to reconstruct their original calendars “to increase scientific understanding of the relationships between people and the seasonal cycles of resource availability. In the future the calendars may provide an important baseline for detecting ecological change associated with climate change.”

In the Cook Islands, variations from the traditional calendar - such as changes to the timing of the arrival (or non-arrival) of migratory birds and fish, or the early or late onset and severity of winds and rains, etc., – can alert us to the possibilities of environmental change.

For example, all Cook Islands islands’ traditional calendars have in common the month of ‘Paroro’. In other Pacific islands, paroro refers to seasonal arrival of swarms of the edible sea worm, (Eunice viridis, ‘palolo’ in Samoa; ‘balolo’ in Fiji). Western science does not record the ‘rising’ or swarming of the palolo anywhere east of Samoa. Yet a letter from the Rev. Eastman, dated January, 1947, includes the following paragraph: “I was resident on Rarotonga Island, Cook Islands, for some years from 1913 on, and the rising of the palolo was a well known and expected occasion at Rarotonga in those days. The old men know pretty well when to expect the rising, and the natives used to collect large quantities of it (the sea worm) for food.” The question arises as to whether the presence of paroro as a named month in the Cook Islands Māori calendar, the annual celebration of its rising as recorded by Eastman, and the scientifically recorded absence of such risings in Cook Islands waters, points to recent ecological change?

In similar vein, Teariki Rongo and Celine Dyer reports that māroro tu (the aggregation of flying fish) in Ngaputoru, which, according to Paiere Mokoroa traditionally peaked in the ‘Iringa season’ (July/August), has now largely disappeared from Atiu and Mauke, with Mitiaro the only one of the three islands where large aggregations of spawning māroro are still observed (Rongo and Dyer; 46).

As an education tool, the calendar could be taught in schools to alert young Cook Islanders to the component elements of their environment, the seasons, the times of first flowering, the arrival and spawning of fish species or migratory birds, the arrival of the Pleaides and other elements of Māori astronomy (the calendars record the Cook Islands Māori names of 12 stars or constellations), the mathematics of intercalation, and so on. Students collecting such data over their school lifetime may additionally contribute longitudinal evidence of the changing environment including the impacts of climate change. The ten inhabited islands of the Cook Islands have ten calendars each of which is encoded with scientific data of contemporary significance – they deserve closer attention.

References

W. W. Gill, 1876, Myths and Songs from the South Pacific, London: Henry S. King,

Korero o Aitutaki, 1992, Te Korero o Aitutaki, MOCD, Rarotonga

Paere Mokorea, “Traditional Cook Islands fishing techniques”, Journal de la Société des Océanistes Année 1981 72-73 pp. 267-270

Teina Rongo and Celine Dyer, Using local knowledge to understand climate variability in the Cook Islands, Office of the Prime Minister, Rarotonga, 2015