Reuben Tylor: Looking at Cooks fisheries

Tuesday 18 July 2023 | Written by Supplied | Published in Editorials, Opinion

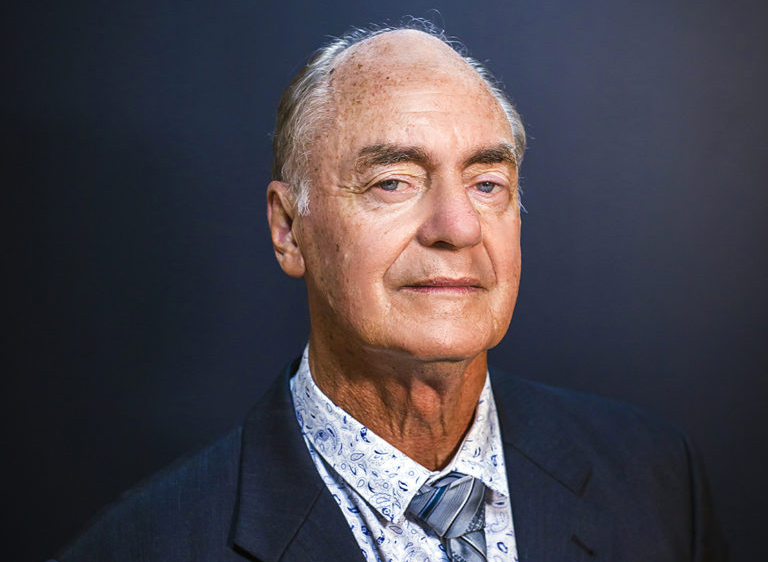

Retired lawyer Reuben Tylor. 23070803

In this, my second article, I want to look at some of the reasons our fisheries resource appears to be in serious trouble.

Two years ago the Ministry of Marine Resources called a meeting with fishermen to explain why the catch had declined so rapidly.

At the meeting I asked whether the foreign fishing boats, and in particular the purse seiners, were in any way responsible for the declining catches.

MMR denied that the foreign fishing boats they had licenced to fish in our waters had any impact at all on the decline in catch in the Southern group.

MMR gave two reasons for their statement.

First, they said because our tuna resource is so large and the foreign boats catch is so small, the foreign boats catch has no impact on our fish stocks.

Second, most of the fish being caught by the foreign boats are in the Northern group, and they said our fish in the Southern group don’t come from these same stocks.

So again, no impact on our fish stocks in the Southern group.

MMR’s reason for the decline in catches instead was the weather pattern called La Nina which has changed the migration patterns of tuna.

The “large resource” argument depends of course upon it actually existing, and this is where the problem begins.

You cannot accurately measure the size of a fish stock, so scientists use several formulae to calculate this.

The most important of these formulae uses the reported catch over several years to estimate the stock.

As long as the quantities and size of fish caught over a time period are stable, then the stock is safe and the fishery is sustainable.

If the reported catch or the size of fish begins to fall, then fishing activity needs to be cut back until it becomes stable again. This formula has many faults, one of which is that it relies on accurate and prompt reporting as well as prompt analysis of the catch figures.

If the stock is depleted quickly, and/or the reporting and analysis is not accurate or not up to date, then the stock can be wiped out before fishing is cut back.

If we accept the formula as valid for the moment, then based on the catch of local fishermen, and that of the only locally owned commercial boat, there is certainly no large stock of fish.

MMR clearly doesn’t rely on our local fishers catch information for its stock assessment, so how does it justify the large stock argument? MMR’s latest report on the Cook Islands catch was published in 2017, so I suspect its analysis of our stocks is well out of date.

Likewise, the latest SPC regional report on tuna stocks relies on reported catch information which is already 3 years out of date.

The SPC says the regional resource of yellow fin tuna and even big eye tuna is in good shape, which is clearly not the case in Rarotonga.

It is not logical that MMR on one hand acknowledges that the catch, not just in Rarotonga but throughout the Cook Islands, has declined, but on the other hand maintains that we still have these large stocks of fish.

If you rely on catch to assess fish stocks, and the catch has fallen dramatically, then surely you need to adjust your assessment of the size of that fish stock.

The second argument, that we are too far away for fishing in the Northern group to affect the catch in Rarotonga has, to my knowledge, no scientific backing.

We are told migratory tuna swim thousands of kilometres to the Northern group from Indonesia, yet they can’t swim another 600 km to Rarotonga?

Where is the tagging program or the genetic testing to show tuna in the Southern group are a different tribe to those in the North?

Unless MMR can produce this, then this argument is pure speculation and no reliance should be placed on it.

I accept MMR’s argument that La Nina has had an impact on our declining catch, but not that it is the only cause of the decline in catch. For example, if we look along our eastern boundary, the islands of French Polynesia do not allow purse seining or foreign long line boats. Their fish catch has not been similarly affected by La Nina. Also, during the covid lockdown foreign fishing boats activity in the whole region as well as in our waters, was reduced substantially. Even though La Nina was in full swing, for several months during this period we had a glut of tuna caught by our local fishermen with tuna being sold for as low as $7 p kilo. This suggests the reduction in numbers of foreigh fishing boats did have an effect on our catch. I have also checked and can find no corelation between prior La Nina events and a decline in catches.

Finally, La Nina is now over, we are now in El Nino, yet there is still no fish.

So what impact does La Nina have?

There is a common misconception that all our tuna come from the seasonal migrations passing through our waters each year.

This is used to justify catching as much as we can, while they pass through our waters.

Again, there is no scientific proof for this argument and it should be treated as pure speculation.

An alternative theory is that there is a resident stock of fish that remain in our waters more or less permanently.

When this stock is reduced by fishing, then it is replenished by the seasonal migration.

If you accept this theory then what might be happening is that the resident stock has been depleted by overfishing, and with La Nina the migratory stocks have passed us by.

French Polynesia may have avoided this by ensuring its resident stock was maintained at a safe level regardless of La Nina events.

The only good news here is that if the migratory schools do return with El Nino and make it past the armada of foreign fishing boats between Indonesia and here, our resident stock may be replenished.

Do we rely on this or does the remaining resident stock needs to be protected in the hope that it will be able to spawn and recover over time.

There is one more factor which I am concerned may have been a cause of the decline in catch.

Purse seine fishing was justified on the basis, that there were huge schools of skipjack in our waters which could be harvested without any negative impact on their stock, or on the stock of other the fish that ate them.

In this case however, they relied on satellite analysis to establish the existence of these huge stocks.

In addition, we were told the skipjack being targeted were adult fish of approximately 18 inches in length which had already spawned.

This was important because it meant there was always a breeding stock. What we were not told was that the mesh at the business end of the purse seine nets was the same as a New Zealand mullet net, catching much smaller sexually immature skipjack less than 12 inches in length, before they spawn.

Purse seining was also not meant to impact other species such as juvenile yellow fin or big eye tuna, which normally school with juvenile skipjack.

However, juvenile yellow fin and big eye tend to be found in greater numbers in these schools of smaller skipjack, so these species may be impacted as well.

Several countries have recognised this problem and forced the purse seiners to increase the mesh size to protect these juvenile fish.

We allow it to continue. MMR doesn’t give the public up to date information about the purse seine catch, and the skipjack resource. I hope my article encourages MMR to do so.

I suspect the answer to the question as to what has caused the damage to our resource is a mixture of overfishing a resource, combined with the impact of La Nina.

Whatever the reason, MMR should be making decisions based on up to date science, and not speculation.

In my next article I am going to review the consequences to the Cook Islands and its people of the decline in our fisheries resource.

Retired lawyer Reuben Tylor

Vaimaanga

REUBEN TYLOR

Born Dunedin, New Zealand, 1949. Primary and secondary schooling in Cook Islands and New Zealand. Graduated BA (1971) and LlB (1973) from Auckland University. Admitted as barrister and solicitor of NZ High Court in 1974 and commenced employment with Chapman Tripp. Joined Short & Tylor in 1975 in Cook Islands, (first private law firm in the Cook Islands).

Founded Southpac Trust Company Ltd in 1983, and Cook Islands Trust Corporation in 1998, both as 50% shareholder.

Since 1987, principally engaged in providing legal services to offshore industry.

Work has included development of various financial and legislative products, most important of which was development of asset protection legislation targeting the US market in late 1980s.

This was a world first, and the Cook Islands continues to retain top position in this industry despite many countries (and even several US states) copying our legislation.

Subsequent to developing this initial legislation, engaged in marketing asset protection products for more than two decades.

During this period has been a guest speaker at a number of international conferences in both the US and Europe, and has published numerous articles on aspects of asset protection in international journals.

In 2002 founded New Zealand Trust & Investment Corporation Ltd, a New Zealand trustee company, as 50% shareholder.

Developed new products into European marketplace, with emphasis on application of tax treaties.

Responsible for marketing and development of new business.

In response to a number of problems within the offshore industry, promoted the formation of the Financial Services Development Authority as interface body between industry and Government. Appointed by Minister of Finance as industry member.

Founded Trustees & Fiduciaries (Cook Islands) Ltd in 2015.